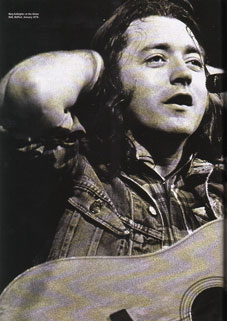

A soulful, passionate musician, Rory Gallagher was up there with the best white bluesmen. He was also, as his brother Donal and others confirm to Classic Rock, one of life's rare genuine nice guys.

Feeling blue: Dave Ling

Given Rory’s aversion to gimmickry (which would

stay with him all his life), Taste favoured denims and long hair and

even scruffier blues-rock. The trio were enthused when record producer

Mervyn Solomon offered the trio the opportunity to make their first

demos. But with no prior consultation, several of the tracks they

recorded were actually released by Major Minor Records, which triggered

another of Rory’s aversions- record labels. The full sessions

eventually surfaced as “Taste: In The Beginning”.

Given Rory’s aversion to gimmickry (which would

stay with him all his life), Taste favoured denims and long hair and

even scruffier blues-rock. The trio were enthused when record producer

Mervyn Solomon offered the trio the opportunity to make their first

demos. But with no prior consultation, several of the tracks they

recorded were actually released by Major Minor Records, which triggered

another of Rory’s aversions- record labels. The full sessions

eventually surfaced as “Taste: In The Beginning”.

De’Ath and keyboard player Lou Martin

enlisting. As another highly popular concert recording called ‘Irish

Tour ‘74’ confirmed, it didn't take long for the band to re-establish

their impressive brand of mental telepathy. McAvoy, himself a former

guitar player, swears that their unspoken communication came naturally.

De’Ath and keyboard player Lou Martin

enlisting. As another highly popular concert recording called ‘Irish

Tour ‘74’ confirmed, it didn't take long for the band to re-establish

their impressive brand of mental telepathy. McAvoy, himself a former

guitar player, swears that their unspoken communication came naturally.

‘Moonchild’, ‘Shin Kicker’, ‘Brute Force And

Ignorance’ and ‘Shadow Play’ to his already strong repertoire. But

prior to ‘Photo Finish’ Rory had chosen to scrap an entire album of

material, and relations with Chrysalis were beginning to sour, causing

him to sarcastically dub his next album ‘Top Priority’. Despite being a

strong, powerful rock record, a third live album, ‘Stage Struck’

pigeonholed his act at completely the wrong moment.

‘Moonchild’, ‘Shin Kicker’, ‘Brute Force And

Ignorance’ and ‘Shadow Play’ to his already strong repertoire. But

prior to ‘Photo Finish’ Rory had chosen to scrap an entire album of

material, and relations with Chrysalis were beginning to sour, causing

him to sarcastically dub his next album ‘Top Priority’. Despite being a

strong, powerful rock record, a third live album, ‘Stage Struck’

pigeonholed his act at completely the wrong moment.

school in his birthplace of Ballyshannon has

recently been converted into an arts centre in his name, and each year

there are various tribute shows around the world. There are also

numerous fan-run Rory websites, one of the best being www.roryon.com.

school in his birthplace of Ballyshannon has

recently been converted into an arts centre in his name, and each year

there are various tribute shows around the world. There are also

numerous fan-run Rory websites, one of the best being www.roryon.com.

| "I was with Free when I first

saw Rory and I remember thinking: "God, what I wouldn't do to have that guy in this band." Paul Rodgers, Bad Company |

"A beautiful man and an amazing player. We will miss him very much" U2's The Edge |

| "Rory was a really big

influence. One of the all-time great guitar players. Playing with him in LA was one of my biggest thrills ever." Slash |

"One of the top ten guitar players

of all time, but more importantly one of the top ten good guys." U2's Bono |

| "Rory was such as purist. He

wouldn't sell out. He wouldn't do singles, he didn't want to do videos.

How many people in the music business today would have that kind

of stand. It's so dangerous" Gary Moore |

"Rory's

death really upset me. He was such a nice guy and a great player." Jimmy Page |

|

The Loop Mailing & Discussion List  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Forward

to next article |